Over the last 100 years, the nature of the workplace and corporate offices have undergone significant changes. With each generation, the demands and defining features of the workforce evolve, and workplace designers find ways to adapt existing infrastructure to meet the needs and trends of the time. From sterile layouts and rigid staff structures, to dynamic and modular environments, commercial building space has certainly come a long way. Concept after concept has been deployed to create functional office spaces that optimize business and employee productivity, and while some layouts were worse for wear, others were instrumental in setting the stage for some of today’s most progressive workspaces.

Here are four notable eras when the cultural climate of the time converged with office design.

1900s - 1950s: The Taylorist Office & The Efficiency Movement

If there was one word that could encapsulate the beginning of the 20th century, it would be ‘process.’ Hot off the heels of the Industrial Revolution and amid the Great Depression, employees were “workers,” individuals were cogs, and time was of the utmost importance. Filling a specific role in the assembly line, employees were taught to repeat one assigned task, thrive (within the boundaries of their role), and meet their quota.

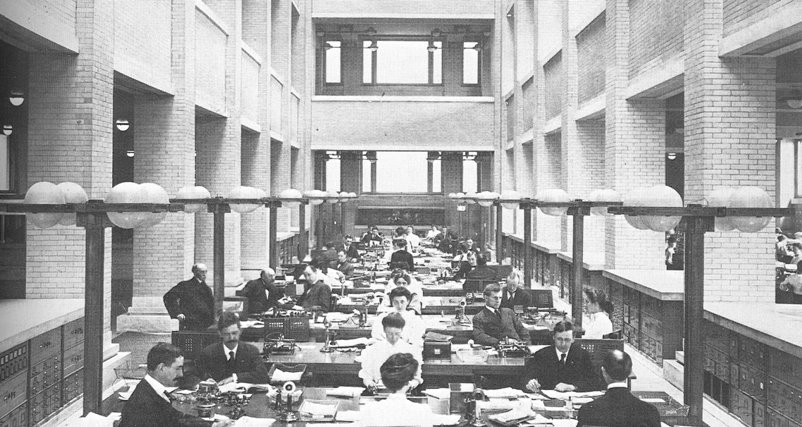

In this era, the Taylorist Office design was established to enable mass production of goods by white collar workers—bringing processes of the Industrial Revolution into the commercial office building. Widely considered the first instance of the Taylorist Office was Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Administrative Building, headquarters of Larkin Soap Company of Buffalo, New York. With 1,800 workers and 5,000 mail orders per day, the company featured desks with built-in cabinets and dividers to keep workers organized and visually focused. The building solidified the time’s deep dedication to assembly-line structures and the Efficiency Movement—an economic push to eliminate waste and develop best practices.

Frederick Winslow Taylor, the father of “scientific management,” later expanded, branded, and popularized Wright’s design. His layout maintained one central work area, with elevated desks and executive level offices—providing managers and supervisors a view of the floor, so they could literally look down on their workers. The Taylorist Office was found throughout business sectors—law and accounting firms, insurance companies, and government agencies—because they believed his design was the key to creating a non-stop workflow. With the introduction of new tech and building advances, like electrical lighting and steel frame construction, as well as data processing and communication devices (calculators, typewriters, the telegraph, telephones), white collar work and workspaces closely mirrored blue collar production—large-scale, impersonal, and mechanical.

1960s: Bürolandschaft (The Office Landscape) & The Age of Freedom

With broad anti-war and WWII sentiment, the Civil Rights movement, second-wave feminism, gay rights, and the “New Left,” freedom was in full force and a counterculture of free love, equality, and experimentation was in bloom. With Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs at the tip of every academic’s tongue, and MIT’s studies on “organizational development” and “office culture,” the linkage between emotional state and productivity was becoming increasingly important. This new emphasis on employee well-being spread into office design, as illustrated with walkable space, indoor plants, and employees of all levels coworking.

With the introduction of the Bürolandschaft (The Office Landscape), brothers-by-blood and furniture-designers-by-trade Eberhard and Wolfgang Schnelle broke “the rigid and ineffective structures of large bureaucratic organizations” from the previous era, and provided a less siloed and more collaborative work environment. The design enjoyed a brief stint of popularity in Europe, but its hyper-progressive intent of cross-team and cross-title collaboration made it both “too radical” to be adopted globally and impressively ahead of its time.

1970s - 1990s: The Cubicle Farm & The Rise of Corporate America

From 1950 to 1989, there was a massive increase in national production of services and a decline in production of goods. The 1980s alone witnessed a 6% shift in employment from goods-producing to service-producing. Over three-fourths of all jobs were now dedicated to services, such as computer and data-processing, banking, and health—moving more people into commercial buildings and office spaces. To accommodate this job growth (with limited real estate), a fast and cost-effective solution was needed. Enter the Cubicle Farm and the rise of Corporate America.

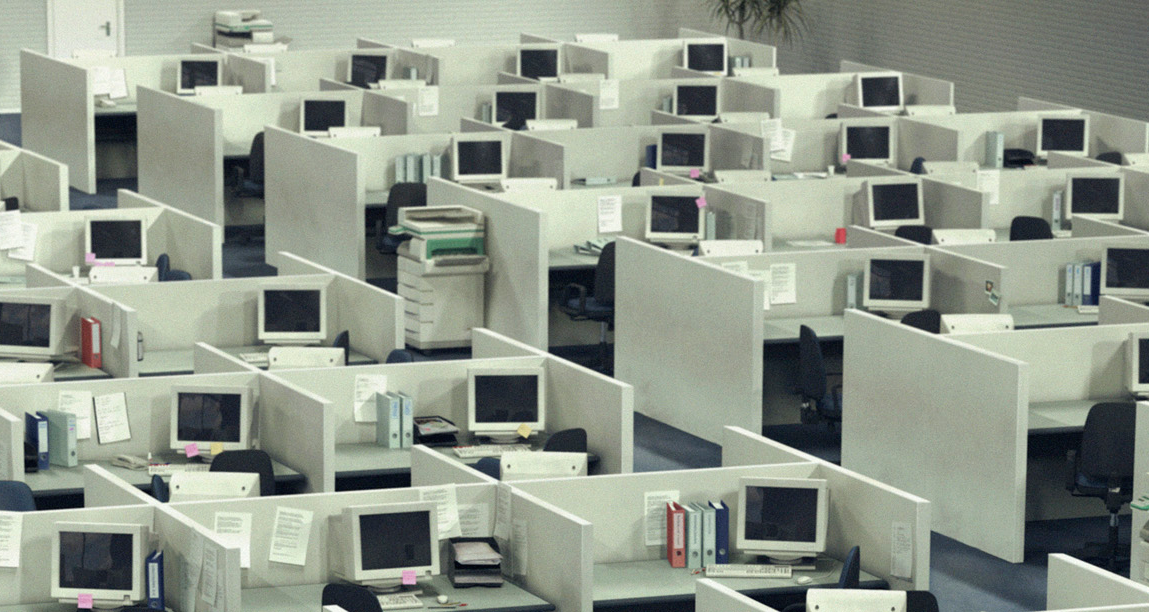

During this time, Robert Propst was among the first designers to argue that office work was “mental work and that mental effort was tied to environmental enhancement of one’s physical capabilities.” His first design, the Action Office I, proved difficult to implement in large offices, as it relied on workspaces of varying heights and bespoke furniture. It was designed with multiple functions in mind, but ultimately only suited small offices—where managers and employees interacted using the same furnishings. His second iteration, Action Office II, had a much stronger emphasis on individual privacy and featured cheaper interchangeable mobile wall units. It was scalable, simple to install, and fit the demands of many large organizations’ growing workforces and specialized services.

Soon, knockoff designs of the Action Office II took privacy a step further with nearly six-foot tall fabric panels. Take the Sunar system by Douglas Ball, from the floor plan everything looked relatively fine, but Ball himself reported that when he “went to see the first installation of the Sunar system, a huge government project…it was awful...we had never considered the vertical elevation,” and with that the cubicle was (accidentally) born.

2000s: The Virtual Office & Agile Working

More than any other factor, the 21st century has been defined by widespread internet access. Forever-shifting how we connect, the world wide web brought a new freedom to the workplace. The recession of the early 1990s “combined with growing competition in increasingly globalized markets put a squeeze on many businesses, whose CEOs and Managing Directors could not ignore the cost savings of teleworking and outsourcing facilitated by advanced telecommunications.” According to Global Workplace Analytics, as of January 2016, “50% of the US workforce holds a job that is compatible with at least partial telework,” and “80% to 90% of the US workforce says they would like to telework at least part time.” Agile working has undoubtedly become both a strong employer need and employee demand.

With agile working, employees come and go freely, working from the office, home, coffee shops, or airports. Modern workplace designers have a unique challenge—to create spaces that employees truly want to be in. Ones that can easily be transformed for a myriad of tasks, work styles, and staff capacity.

For the first time in history, the workplace is simultaneously hosting multiple generations of employees. Having experienced various workplace demands and designs, Baby Boomers, Gen Xers, and Millennials have different value systems and work requirements. Their shifting and broad-ranging needs and expectations are driving an era of people-centric and employee-focused designs and products.

So, what’s next? Building design and function will continue to evolve to meet the demands of the workforce, technology of the times, and cultural trends. Both businesses and buildings must get smarter to adapt and keep ahold of their biggest resource: their employees and occupants.

Adapted and excerpted from Morgan Lovell: The Evolution of Office Design. Other sources include Wired, Applied Workplace, and Human Spaces.

Want more? Subscribe to follow along and get social with #AtoZSmartBldgs.